Creating a future of effective science communicators

The need for incentivized science communication training for graduate students

In 2017, I attended the March for Science in Denver, CO alongside two plant biology graduate students. The excitement I got from being in a mass of people who support science funding dissipated when we started talking to a group of fellow march attenders about GM crops. Even though these non-scientists were in support of science advancement, they assumed that, as plant biologists, we would agree with them that GMOs are unsafe for consumption, especially compared to natural, organic foods. Unfortunately, instead of taking this as an opportunity to open a dialogue, all three of us graduate students shied away from the conversation because we had no idea how to approach the subject in a nice and productive manner. Like my 2017 self, most graduate students do not have relevant training on how to effectively communicate science with the public. Only now, after a yearlong fellowship in which I received science communication training, do I feel I have the tools to engage in a productive conversation with skeptical group such as the one I met at the March for Science.

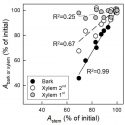

There is a growing consensus within the scientific community that scientists have a duty to communicate with the general public to improve understanding of science topics. The ability to effectively communicate science with the public is essential to a scientist in any field, but especially in plant biology where issues like climate change and genetic modification are vital areas of research to contribute to a sustainable society and future. But science communication is a difficult skill to learn, especially on one’s own. Complicating science communication is the fact that different science topics are not viewed equally by the public (Rutjens et al., 2017). For example, a 2017 Pew Research Center study found that when American adults were asked about specific scientific issues, a majority trusted scientists to give accurate information on vaccine benefits. But, only 39% trust scientists on issues of climate change and 35% trust scientists on benefits of genetically modified foods (Fig. 1).

Effective science communication is a difficult task for three main reasons: 1. Scientists focus more on education than dialogue; 2. Scientists have difficulty recognizing and rephrasing jargon; 3. Formal science communication training has not been prioritized by the scientific community.

The education versus dialogue issue reflects that scientists have historically clung to an approach termed the deficit model of communication (Simis et al., 2016). The deficit model focuses only on scientist’s ability to provide facts and knowledge to the lay person (see Figure 2). Certainty, facts are important in a lay person’s acceptance of scientific findings. However, by focusing only on education, and discounting conversation, scientists have ignored the value systems of lay people. This is a critical omission because values largely mold people’s decisions and attitudes towards scientific topics, especially those issues that have been politicized (e.g. GM crops). For example, a person may see the value in alleviating health risks for their child through vaccination. But the same person may not see value in GM crops because scientists have failed to draw on the value of food security when engaging in a dialogue about GM crops with that person. For a lay person to trust in scientists, it is essential that they feel scientists have their best interests and values in mind. For a scientist this is a daunting task, because research itself is not commonly based in values, but in pursuing interesting questions to address key knowledge gaps. Therefore, to engage in a dialogue with the public, it takes experience in communication for the scientist to begin to understand how their research appeals to different value systems, and even more time to learn how to discuss scientific findings while respecting those values.

Apart from learning how to create a dialogue with the public, science communication is also daunting because breaking down jargon while still communicating the importance of research is incredibly difficult. For most scientists, jargon is a part of their everyday language and they forget that the public does not understand certain terms. For a lay person, hearing and not understanding scientific jargon is frustrating, and often leads to confusion on a subject. Training for scientists in how to use language carefully, and how to understand and relate to values of any audience will accelerate our ability to create a dialogue with the general public.

Finally, learning how to create a dialogue and choose language has not been a priority for the scientific community. In the past two decades, organizations like COMPASS and AAAS have begun to address the problems of the deficit model of communication. These organizations have started offering science communication workshops to teach scientists how to effectively connect with different audiences by focusing on dialogue and language. However, these communication trainings are voluntary, and often expensive. As a result, most scientists – and especially graduate students – do not consider any formal training in communication with the public as part of their broader training as a scientist. More scientists would engage in these trainings if it was made a priority in the scientific community through incentivized training programs or formal curriculum.

Graduate students are a great candidate demographic to target incentives for formal communication training for multiple reasons. First, we are just starting in our fields, so we are more aware of the jargon that might be off-putting to a general audience. Second, we are in a phase where our role is that of “trainee”. We are trained in communication to other scientists, data analysis, philosophy of science, lab management, and even teaching/mentoring. This training is ultimately restricted towards engaging with people in the relatively small bubble of academia, and not the much larger pool of the general public. However, issues of science in the public are directly linked to research coming from academia. For these research findings to be incorporated into policy and society, academics need to effectively communicate their findings.

Because graduate students are in a phase of training, we have time to be formally trained in focusing on removing jargon and connecting with the public through shared values stemming from our research. Graduate students greatly value their time and will be more likely to see value in science communication if training was incentivized or part of formal curriculum. In my yearlong fellowship training in science communication at Colorado State University, I have learned how to connect with audiences of differing values and levels of scientific literacy to communicate my research with journalists, skeptical audiences, the CSU provost’s office, and more. This fellowship works off a cohort-based model where all fellows see each other struggle and improve in their science communication through workshops and a mini-conference. Participation in this fellowship was incentivized by the fact that the cohort model serves to bring advanced PhD students and post docs from different fields together to foster new collaborations. However, only 40-60 people from across CSU apply to this fellowship each ear, and only 20 are selected. A small pool of total CSU graduate students and post docs are interested in applying for this communication training, meaning many others may not see the inherent value in science communication. Increasing access to incentivized or formal communication curriculum for graduate students would shift the science community to prioritize effective communication with the public.

For science communication to improve, we need graduate schools across the country to invest in incentivized or formal science communication coursework for graduate students. With formal communication training as a part of graduate work, future PhDs will stop shying away from difficult topics from strangers and instead try to engage in dialogue to improve both the public understanding of controversial topics and the quality of our science to support a diverse group of needs. Indeed, just as cutting-edge technologies, discoveries, and creativity are key to advancing science, so too is creating an effective dialogue with non-scientists to communicate our findings and their importance.

About the Author: Gretchen Kroh is an NSF Graduate Research Fellow. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation

Rutjens BT, Sutton RM, van der Lee R. (2017) Not all skepticism is equal: exploring the ideological antecedents of science acceptance and rejection. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 44: 384-405. 10.1177/0146167217741314

Simis M, Madden H, Cacciatore MA, Yeo SK (2016) The lure of rationality: Why does the deficit model persitst in science communication? Public Understanding of Science. 25: 400-414. 10.1177/0963662516629749

Courchamp F, Fournier A, Bellard C, Bertelsmeier C, Bonnaud E, Jeschke JM, Russell JC. (2016). Invasion Biology: Specific Problems and Possible Solutions. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 32: 13-22. 10.1016/j.tree.2016.11.001.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!