The Art of Academic Mentorship

What is Academic Mentorship?

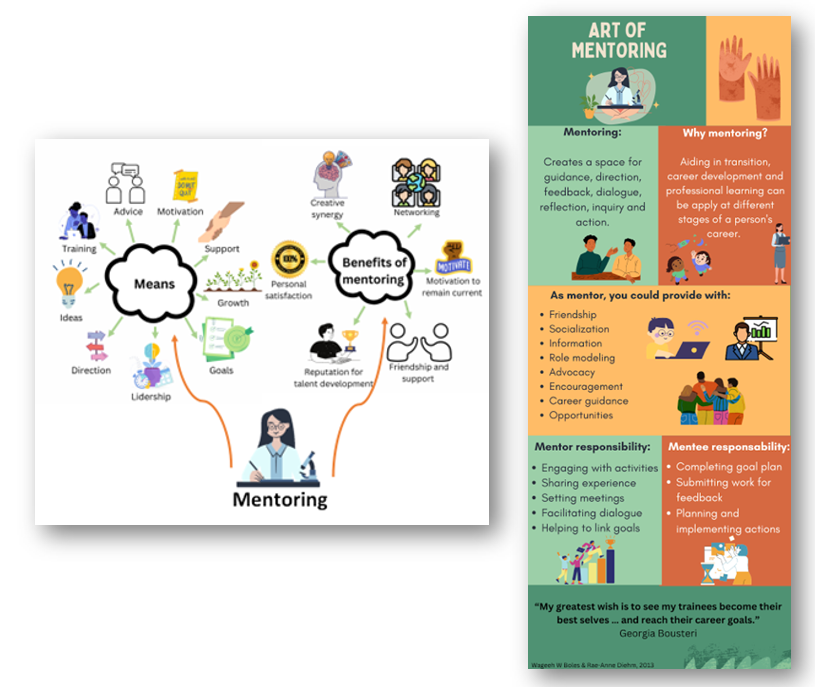

Mentorship is defined as an act of supporting individuals to improve and achieve their goals in one or more areas of their personal life or career. Mentors are expected to help mentees set realistic achievable goals, to encourage or challenge people to reach them at their own pace, and to use their own experience, knowledge, and skills to provide valuable input. Patience and genuine interest in the mentee are two key traits to successful and sustainable mentoring.

Selecting a Mentor Based on Career Stage

Starting a new position, whether in academia or industry is often a hopeful experience, but most of the time it is accompanied by fear and anxiety. The transition process into a new environment, culture, language, and set of expectations can be challenging, but having the support of a mentor can be invaluable. A mentor can provide guidance, advice, and be a sounding board for any concerns or questions that arise during the transition for early career researchers (ECRs). In addition, a mentor can offer insights and strategies for navigating the new work environment and establishing oneself in a new role (Sarabipour et al., 2021). Therefore, it is highly recommended to seek out a mentor to help facilitate a smooth and successful transition into a new position.

According to a 2019 Nature survey, most PhD candidates have reported experiencing a lack of guidance and attention from their mentors (Woolston, 2019). Selecting a mentor is a pivotal decision for career advancement. You have to determine whether you need a mentor before you seek one (Sarabipour et al., 2021). Ask yourself what benefits a mentor can bring in your career development. It is crucial to consider our career stage when choosing a mentor. To pick a suitable mentor, we should consider our career goals, strengths, and weaknesses. Additionally, we should look for mentors who have experience and expertise in our field and are willing to share their knowledge and insights. We can also seek recommendations from colleagues or professional associations, attend networking events, and do research online to identify potential mentors (Sarabipour et al., 2021). Once we have identified potential mentors, we should reach out to them, introduce ourselves, and express our interest in building a mentoring relationship.

- Early career: If you are just starting out in your academic or nonacademic career, you may benefit from a mentor who can provide guidance on navigating the academic or nonacademic environment, developing your skills, and building your network. Look for mentors who have experience in your field and are willing to invest time in helping you.

- Mid-career: If you have been in academia for a few years and are looking to advance your career, you may benefit from a mentor who can provide advice on how to secure funding, publish your work, and advance to the next level. Look for mentors who have achieved the career goals you aspire to and can offer guidance on how to reach them.

- Late career: If you are a senior academic who has achieved significant success in your career, you may benefit from a mentor who can provide guidance on succession planning, transitioning to retirement, and leaving a lasting legacy. Look for mentors who have experience in these areas and can offer insights on how to navigate these challenges.

Casual Mentorship or Formal Mentorship in Academia?

Casual mentoring can happen intentionally or spontaneously. Simon Sinek, an inspirational speaker, states that a true mentor relationship develops to a point where the mentor sees the mentee as a mentor too, forming a two-way mentoring relationship where both parties learn from each other (Sinek, 2021). Casual mentoring allows for this as the relationship is allowed to develop naturally. The main downsides of casual mentoring are maintaining commitment from both sides of the party and being held accountable.

Formal mentoring programs are structured such that an organizer oversees the programs and does the mentor-mentee matching to ensure both parties have specific goals and targets. In the fast-paced corporate world, there are many successful mentoring programs (Reeves, 2022). However, there is the risk of mentees feeling that the relationship was artificially put together (Straus et al., 2009). A huge logistical and administration effort would have to be invested to develop a structured program.

Alternatively, academia could adopt a casual mentoring platform without the administrative load of formal mentoring programs. The University of Edinburgh has developed a mentoring platform called Platform One to allow their staff and students to create profiles and connect with mentors and mentees from different fields, consequently promoting interdisciplinary mentoring (The University of Edinburgh, 2021). However, the impact and success of Platform One is yet unknown.

Whatever type of mentoring works best for academia, the main challenge is that academics are already overburdened with admin work, long hours, and grant writing alongside teaching and many other duties (Bothwell, 2018). With their already declining work-life balance (Bleasdale, 2019; Woolston, 2020), it could be difficult to find time for mentoring as it usually requires a long-term time commitment to see the fruits of success. This systematic issue will not be solved in the near future, so it’s up to academics to determine how much time they can invest in mentoring. Marino (2020) discussed other challenges of academic mentoring that could be of interest to read.

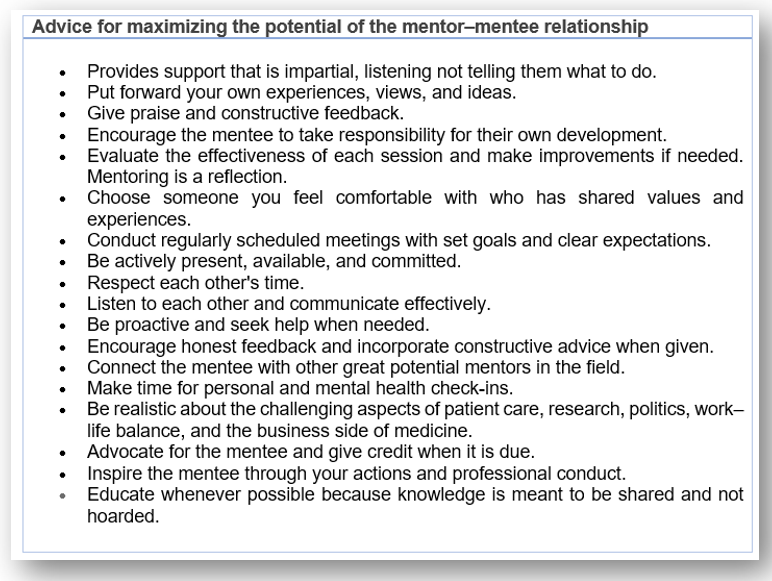

Top Tips for Mentors to Achieve Successful Academic Mentoring

- Know your strengths and weaknesses.

Be honest about what you know and, more important, what you don’t know. It’s important to also know your own biases. Personal relationships or upbringing are laced with hypocrisy and prejudice. That’s why mentors have to draw the line carefully in terms of seeking equality, diversity, and inclusion in all they do. A mentor should be prepared to share their weaknesses and failures as well. This shows a mentee that the mentor is honest and open and helps to build trust between one another.

- Don’t always be the hero.

To promote growth, sometimes it might be better to give space for mentees to make mistakes, and to not always give all the answers. Learning through errors is beneficial to learning, however, it is highly dependent on subsequent corrective and constructive feedback (Metcalfe, 2017). Mike Mears, a leadership advisor, stated that the key to creating a healthy relationship is having open communication about their mistakes (Mears, 2022). Additionally, if a mentor cannot support their mentee in any aspect, they should always encourage mentees to seek other mentors.

- Commit and prepare.

Both mentors and mentees should be prepared for each meeting. A written agenda is the number one requirement in any meetings to help keep the meeting succinct and productive as time is limited in academia (Fetzer, 2009). Commitment is also a key factor to mentoring success. Put it simply, if one does not have time to mentor or to be mentored, don’t do it. Poor mentoring has been shown to be worse than no mentoring at all (Ehrich et al., 2004). Without genuine interest in the mentee, there will be a lack of drive or motivation to keep a mentor mentoring. If circumstances have changed and one cannot commit to mentoring anymore, a mentor should notify their mentee and try their best to guide them to another mentor.

- Build the “not yet” mindset in mentees.

A TEDxTalk by psychologist Dr. Carol Dweck discussed building a growth mindset within individuals and organizations by using the “power of yet” (TED, 2015). For example, if a mentee says “I’m not good at X,” a mentor can strategically add the word “yet” behind “X” to encourage continual development, bounce back from a failure or mistake, or even to keep mentees engaged in a task (Guthridge, 2021). Although the “power of yet” has not been studied in detail, there could be huge benefits in simply adding a single word to the end of a sentence.

- Keep mentoring mentee-focused.

There will be times where academic mentors can forget that the goal of mentorship is to help a mentee with their goals. Sometimes, not all ECRs have goals to pursue academia, and a mentor should respect that decision instead of trying to persuade them to stay in academia. A mentor should be open-minded, mentee-focused, and not simply seek mirror images of themselves.

- Sett clear boundaries and expectations.

There might be a dilemma on how much is too much or too little help. ECRs are in progress to develop as independent researchers. Just remember, mentoring includes helping ECRs set realistic goals and guiding/advising them on their development plan, not making a decision for them. It is also important to communicate to a mentee that mentoring is different from friendship (i.e., companionship) and there should be clear boundaries (Detsky & Baerlocher, 2007). For example, it is unusual to share personal contact numbers and social media accounts between a mentor and mentee, or invite each other for dinner together. However, at the end of the day, it is dependent on how a mentor wants to structure their mentoring experience, but some boundaries are better than no boundaries at all.

Modified from Lin et al., 2021

Mentoring after Pandemic Times

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, a mental health crisis was already affecting students at different levels, as well as postdocs. This crisis has only worsened since the pandemic, as uncertainties surrounding graduation dates, contract renewals, research funding, and manuscript review processes have added to the heightened stress experienced by both mentors and mentees (Pfund et al.,2021; Termini et al., 2021; Levine & Rathmell, 2020). It is understandable that mentors may not have the necessary training to address mental health issues. To provide additional support, Termini et al suggest that mentors should seek help from professionals at their institutions (Termini et al., 2021).

Based on recent events, people’s priorities and circumstances have changed, it is necessary to shift in the way we approach mentoring. As we adapt to new challenges and uncertainties, it is important for mentors to adjust their strategies and support their mentees in different ways. Gotian and Pfund brought six mentoring tips to improve mentor-mentee relationships: 1) Plan-in person interaction, 2) reassess goals, 3) realign expectations, 4) break goals down into chunks, 5) attend to psycho-social needs, and 6) lead by examples (Gotian and Pfund, 2021). For example, mentoring has been affected by the shift from in-person to remote mentoring, which has posed a challenge due to the lack of personal connection between mentors and mentees. To address this issue, mentors should consider bringing back face-to-face activities.

Concluding Remarks

Mentorship is an essential component of personal and professional growth, but it can also be a challenging role due to the unique needs and requirements of each individual. Building a successful mentor-mentee relationship requires effort, dedication, and patience. It is crucial to remember that mentorship is a two-way relationship, and both parties must actively participate to ensure its success. As a mentee, it is essential to seek honest mentors who provide constructive feedback to help you develop your career. As a mentor, please invest time and effort with mentees. Overall, mentorship is a valuable tool for individuals seeking to improve their personal or professional development, gain insight and knowledge from a more experienced individual, and ultimately, achieve their goals.

References

- Lin, G., Murase, J.E., Murrell, D.F., Godoy, L.D.C., Grant-Kels, J.M. (2021). The impact of gender in mentor-mentee success: Results from the Women’s Dermatologic Society Mentorship Survey. Int J Womens Dermatol. 7(4):398-402. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.04.010.

- Gotian R & Pfund C, 2021. Six mentoring tips as we enter year two of COVID. Nature. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-01598-4

- Sarabipour, S., Hainer,SJ., Arslan, F.N.,de Winde, CM.Furlong,E., Natalia Bielczyk,N., Nafisa M. Jadavji,N.M., Aparna P. Shah, A.P., and Davla, S.(2022). Building and sustaining mentor interactions as a mentee. FEBS J. 289:1374-1384. doi: 10.1111/febs.15823

- Termini, C.M., McReynolds, M.R., Rutaganira, F.U.N., Roby,R.R., Hinton,A.O., Carter,C.S.,. Huang, S.C., Vue, Z., Martinez, D., Shuler,H.D., Taylor, B.L. (2021). Mentoring during Uncertain Times. Trends in Biochem Sci. 46(5):345-348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2021.01.012

- Pfund, C., Branchaw, J.L., McDaniels, M., Byars-Winston, A.,Lee, A.P., Birren, B. (2021). Reassess–Realign–Reimagine: A Guide for Mentors Pivoting to Remote Research Mentoring. CBE—Life Sciences. 20:es2 Education. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.20-07-0147

- Levine, R.L., Rathmell, W.K. COVID-19 impact on early career investigators: a call for action. Nat Rev Cancer 20:357–358 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-020-0279-5

- Boles, W.W. and Diehm,R-A. (2013).Creating more rewarding careers: A mentoring guide for the professoriate. QUT Department of eLearning Services.

- Woolston, C. (2019). A message for mentors from dissatisfied graduate students. Nature. 575: 551-552. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03535-y

- Fousteri, G. (2022). A mentor’s journey. Science. 375:350. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ada009

- Sinek, S. (2021, September 10). How Great Mentor Relationships Are Formed. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fATAT6L9o5k&ab_channel=SimonSinek

- Reeves, M. (2022, September 21). 10+ Examples of successful mentoring programs. Together. https://www.togetherplatform.com/blog/examples-of-successful-mentoring-programs

- T. (2014, December 17). The power of believing that you can improve | Carol Dweck. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_X0mgOOSpLU&ab_channel=TED

- Guthridge, L. (2021, April 26). How To Use The ‘Power Of Yet’ To Encourage Learning And Growth. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2021/04/26/how-to-use-the-power-of-yet-to-encourage-learning-and-growth/?sh=961db873e122

- Straus, S. E., Chatur, F., & Taylor, M. (2009). Issues in the mentor–mentee relationship in academic medicine: a qualitative study. Academic medicine, 84(1), 135-139.

- The University of Edinburgh (2021, November 4). Mentoring Connections. The University of Edinburgh. https://www.ed.ac.uk/human-resources/learning-development/other-development-options/mentoring-connections

- Bothwell, E. (2018, February 8). Work-life balance survey 2018: Long hours take their toll on academics. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/work-life-balance-survey-2018-long-hours-take-their-toll-academics

- Bleasdale, B. (2019). Researchers pay the cost of research. Nature Materials, 18(8), 772-772.

- Marino, F. E. (2021). Mentoring gone wrong: What is happening to mentorship in academia?. Policy Futures in Education, 19(7), 747-751.

- Ehrich, L. C., Hansford, B., & Tennent, L. (2004). Formal mentoring programs in education and other professions: A review of the literature. Educational administration quarterly, 40(4), 518-540.

- Woolston, C. (2020). Postdocs under pressure:‘Can I even do this any more?’. Nature, 587.

- Mears, M. (2022, January 26). To grow, your employees must sometimes fail and make mistakes. Do you let them? And do you own your mistakes? Here’s how great leaders promote growth. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/grow-your-employees-must-sometimes-fail-make-mistakes-mike-mears/

- Fetzer, J. (2009). Quick, efficient, effective? Meetings!. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry, 393(8), 1825-1827.

- Metcalfe, J. (2017). Learning from errors. Annual review of psychology, 68, 465-489.

- Detsky, A. S., & Baerlocher, M. O. (2007). Academic mentoring—how to give it and how to get it. Jama, 297(19), 2134-2136.

______________________________________________

About the Authors

Yen Peng (Apple) Chew is currently a fourth-year PhD student at the University of Edinburgh and a 2023 ASPB Plantae Fellow. She works on developing CRISPR gene editing technologies in green microalgae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. You can find her on Twitter at @applechew.

Andrea Gomez Felipe is a postdoc at the University of Montreal and a 2023 Plantae Fellow. She wants to understand the molecular, cellular and tissue level mechanisms underlying organogenesis in plants using cutting-edge approaches. Her professional interest lies in combining molecular biology, microscopy, and computational tools to elucidate specific mechanisms of plant development. Besides her research, she loves swimming, biking, hiking, and reading. You can find her on Twitter at @andreagomezfe.