The Value of Mentoring (Women in STEMM Australia)

This article was originally published on Women in STEMM Australia. Read the original article

The Value of Mentoring

Trainees in science often express the need for ‘a mentor’. What does this mean and what should mentees and mentors expect?

What is a mentor? The Macquarie dictionary definition is ‘a wise and trusted counsellor’. A mentor is someone with more experience, often older (although not always), who helps and guides another individual’s development. This may be to help do a job more effectively, develop a specific skill and/or progress in their career – often without any personal gain for the mentor. Scientists often retrospectively recognise they were mentored throughout their career; they just describe mentors and mentoring by other names.

What is mentoring? Many students, early career researchers and established investigators are not entirely sure what mentoring means – and expectations can vary. Mentoring continues throughout one’s career, at every level. To mentor and be mentored is not only to pass on knowledge gained over a lifetime, but to also share wisdom from past mistakes and provide guidance for future decisions. In science, the benefits of mentoring are becoming more widely recognised and valued. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the US recognises proficient mentors as part of their grant evaluation process and actively encourages the practice through Mentored K Awards. These awards transition young investigators to independence under the mentorship of a senior investigator. The PhD and postdoctoral phase is one of ongoing education and training, with the ultimate goal of scientific independence. It is therefore essential that early career researchers identify one or more mentors early in their career and actively establish positive mentoring relationships.

Who should be your mentor? Early career researchers typically seek mentoring from people with more experience or different experiences. These can include senior investigators within their institution particularly those who have won fellowships and/or grants. This may be their supervisor, but for a variety of reasons this is not always the case. Supervisors have an incentive to mentor their students, fellows and staff since they have invested in them, but they are also captive to their own experiences and can sometimes have a conflict of interest. This is why it is important to consider a mentor outside your institution, such as investigators with whom you have served on committees or met at conferences. Developing a good rapport with a mentor is a plus, particularly for an ongoing mentoring relationship, but this is not always essential. Occasional mentorship from a ‘straight-talking’ individual who doesn’t know you well can provide advice with reduced risk of bias; however, they may not fully appreciate your situation.

Women in science sometimes feel they ‘should’ be mentored by another woman; however, all scientists are well-placed to mentor women (and men!). Diversity within the ranks of senior faculty will benefit everyone and contribute to a productive mentoring and research environment. With fewer women scientists in senior positions, however, it is essential women be willing to engage with mentors of both genders. In the US, Women in Biomedical Careers sponsors national workshops on mentoring women in biomedical careers and best practices for sustaining career success. Several leading scientific bodies in Australia also recognise the need to support women in science more effectively, including effective mentoring for women scientists. The National Health and Medical Research Council and the Australian Academy of Science have publicly endorsed such initiatives in the last two years.

A mentor we all have, but don’t always realise we have, is the peer mentor. These are friends and colleagues at the same stage of their career and lives as you. Peers can bounce ideas, share their experiences and advice they have received and, importantly, celebrate your successes!

Words describing a good mentor include respectful, honest, positive, enthusiastic, experienced, optimistic, realistic, encouraging, strategic, supportive, sensitive and ‘human’. In an informal survey by the authors of more than 150 postdoctoral fellows in the Parkville Precinct (Melbourne), the number one word associated with good mentoring was respect. Mentees want to feel respected both in a personal and in a professional sense. This was especially important to more reserved individuals and those from a different cultural background or who identified strongly with a minority group. The second most common word was empowering. One fellow said ‘I want a mentor who helps me to help myself.’ A good mentor will want to see you progress in your career and will enjoy seeing you fulfil your goals and succeed in the future. How do you find a mentor? Mentoring is often informal, subtle and non-exclusive and is easier to get if you are engaged in a range of activities such as committees and social events. It is important to talk to your colleagues – who mentors them? How did they meet? Who do they recommend? Word of mouth is a powerful thing!

How do you find a mentor? Mentoring is often informal, subtle and non-exclusive and is easier to get if you are engaged in a range of activities such as committees and social events. It is important to talk to your colleagues – who mentors them? How did they meet? Who do they recommend? Word of mouth is a powerful thing!

Before seeking a mentor, it is important to self-evaluate – ascertain the areas in which you require mentoring. Critically examine your current situation and be pragmatic about your strengths and weaknesses. Needs differ between individuals, but may include public speaking, scientific writing, negotiating skills, teaching, grant-writing, priority setting, communicating your research, strategic planning or determining what you need to achieve to be competitive in the next stage of your career.

Developing professional networking skills is essential. If you are seeking a mentor in a particular field or career, then aim to meet people who are already where you want to be – attend symposia, seminars, conferences and networking events.

Some organisations have formal mentoring programs. Such programs are often under-utilised and under-valued. Yet they are an excellent avenue to mentors who are prepared to devote time and energy in facilitating the professional development of those around them. A mentoring program is particularly useful if you are shy, lack confidence, have moved interstate/internationally or simply do not know where to begin.

Once you have a mentor – what then? Finding a mentor is not that difficult, but after the initial connection, it can sometimes feel a bit ‘awkward’ – especially if the mentor is someone you do not know well or see often. As for any relationship, maintaining a healthy mentoring relationship takes time and effort. Boundaries and expectations are best discussed at the first meeting, such as where and how often you will meet, whether you are both comfortable with a formal/informal setting or a mix of both. ‘Doing coffee’ provides a relaxed setting, but is not always suitable for difficult or confidential conversations. Using technology can work well (email, text and/or social media), but only if your mentor welcomes this interaction.

SPEAKING FROM EXPERIENCE

Mentor reflections

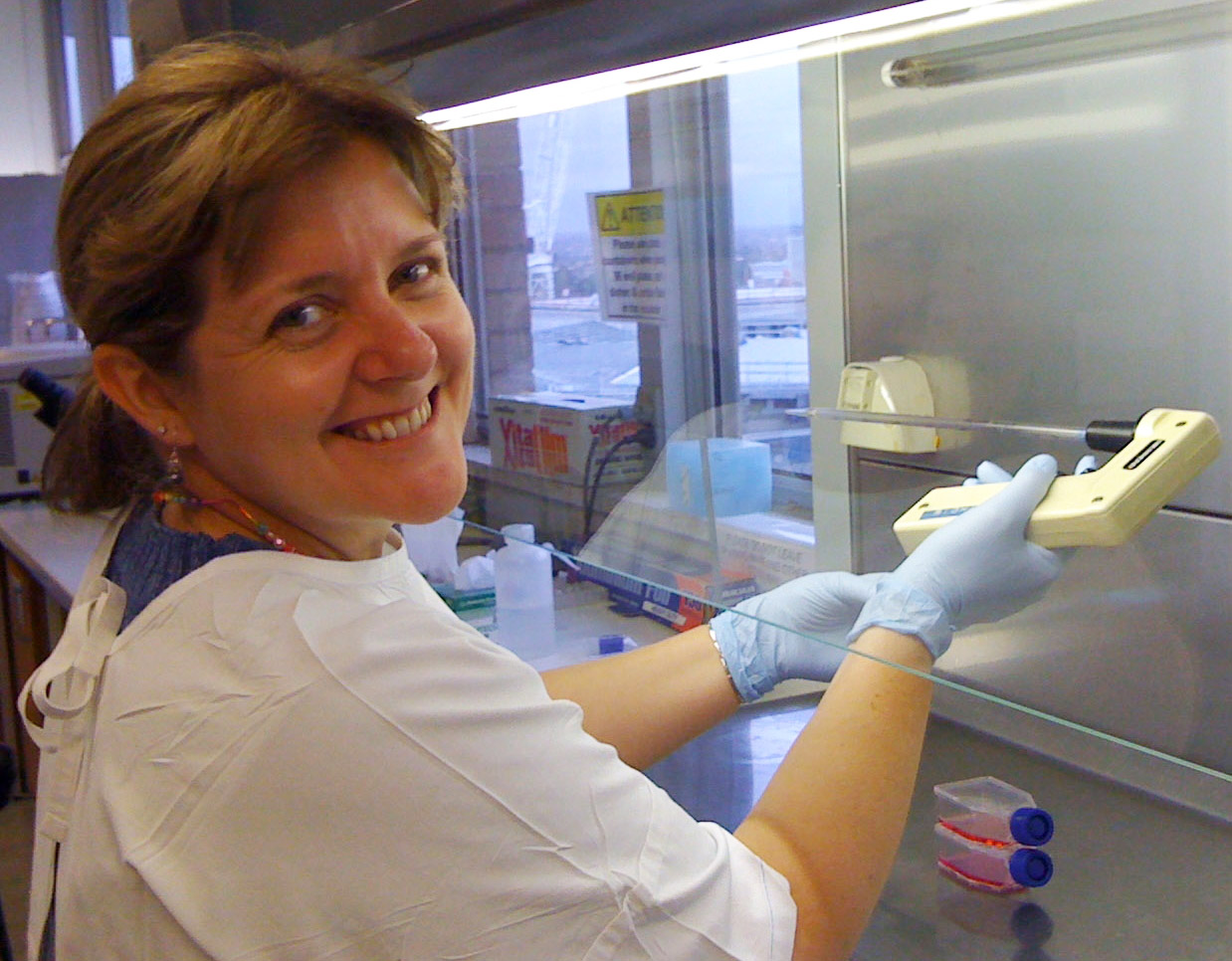

Learning a bit about students as “people” (their personal and professional situation without over-stepping boundaries) is a good basis for ongoing discussions. It is important for me to provide positive feedback and constructive criticism without passing judgement. Since it is easy to forget what it was like being a student, I try to put myself in their shoes. Sharing my own experiences and mistakes can reassure mentees they are not alone, but it isn’t always helpful to their situation, since everyone’s experiences and circumstances are different. With this in mind, I discuss the options, the pros/cons but always state “it is up to you”. Logistically speaking, I check if a mentee requires a confidential meeting, since this is best done in a more formal setting. If a mentee seems to be struggling with their physical or mental health – I encourage them to seek support and point them in the right direction, especially if it is something beyond my capabilities or expertise. (MVEG)

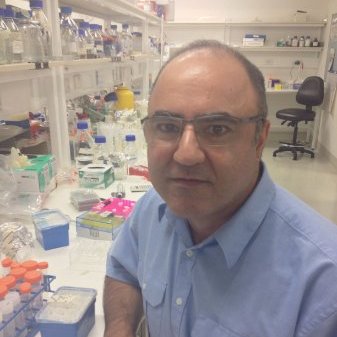

I enjoy passing on the knowledge and experience I have gained during my career to students and peers. It is important to understand everyone is different and their needs and expectations will vary. When mentoring students I have found it best to first discuss their expectations, future career aspirations and past experience. Mentoring can vary greatly and may involve providing technical advice (e.g. problem solving, experimental design, data interpretation, presentations, scientific writing) or advising about career options (e.g. choosing the best lab to do a postdoctoral fellowship and future career goals). There will invariably be occasions when you are asked for advice about a more personal issue (e.g. problems with other lab members or a supervisor). This can be delicate and whether you advise or re-direct is really up to you. If you advise, remember to consider the other person’s perspective and always be positive (often the situation is not as bad as it seems). Science is tough and researchers at all career stages can sometimes feel a bit ‘blue’. This is when your advice as a mentor can be truly appreciated. Carefully listen to your mentee’s concerns. If you are unable to advise, recommend others who are qualified to assist. Always remember that it is up to the mentee to decide whether they wish to take your advice (and don’t be offended if they don’t!). (CAG)

Mentee reflections

The truth can sometimes be difficult to take; however, we must remember it is “constructive criticism”. Your mentor wants to help you, particularly if they will not benefit at all should you take action on their advice. No matter the mentor, I aim to be open to constructive criticism. I believe there is something I can learn from everyone. Committee service has allowed me to develop a ‘mentoring team’. Some mentors I meet regularly (e.g. each month), others less often – and one only when I need the “hard word”. Peer mentoring is some of the most valuable mentoring I have received to date, especially with juggling family and career responsibilities. I haven’t always taken advice and some mentors can actually give very poor advice. Getting involved in non-research activities like fund-raising, policy development and science communication has exposed me to talented professionals who openly share their advice and skills – mentoring by osmosis! All of which has directly benefited my research career. I maintain a healthy work-life balance, but most importantly, I have a dream. (MVEG)

I have had a number of supervisors who have provided invaluable advice and support at different times in my career. I have come to appreciate their candour and the advantages of looking at issues from a different perspective. However, I have sometimes been surprised by the lack of gender and ethnic diversity within senior faculty in universities and research institutions, especially within Australia. For this reason it can be difficult to find a mentor who fully understands the issues faced by those of a different gender or ethnic background. For example, assertive women can sometimes be considered “aggressive”, while people from a conservative culture, a different ethnic background or overseas, can sometimes be criticised for lacking assertiveness if they do not openly question things or share their opinions unasked. I have always valued an intuitive mentor who is sensitive to such issues. (CAG)

What can you do to make the most of mentoring? Mentoring is not a one-way street. You have to give as much as you hope to received – if not more. Maintain an individual development plan that involves honest self-assessment and goal setting. Use this as the basis for discussion with your mentor. Describe your career aspirations and devise a strategy to attain your professional goals. Expect the unexpected – major decision may need to be made quick and a positive ‘can do’ attitude will help. As scientists, we are trained to think critically and be sceptical in our research. This should not equate to cynicism or negativity in all we do or say! Be proactive and harness your initiative. It is your career – take it where you want it to go!

What is the difference between mentoring and sponsorship? Sometimes senior investigators will refer to a long-term mentor who has provided invaluable advice at every career transition, helped them meet the right people at the right time, put their names forward for conference – someone who advocated and promoted their talent both within their organisation and more broadly. This is ‘sponsorship’ and it has proven successful in advancing the careers of women in the corporate sector and in medicine. While every ‘sponsor’ is a mentor; not every mentor can/will sponsor every mentee – and it should not be expected.

How can organisations facilitate mentoring? Quality mentoring is central to the support and training of a diverse, well-educated scientific workforce. The culture of any research organisaton impacts on the morale of its students and staff. Dr Jennifer de Vries argues that viewing mentoring through a ‘bifocal lens’ (where organisational culture inherently fosters the professional development of its staff) increases productivity and yields a better return on investment. The NIH has developed mentoring guidelines and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute supported the Entering Mentoring seminar developed by the University of Wisconsin-Madison, US. All group leaders attend this as part of their introduction to scientific teaching, and it is widely shared. Training investigators to mentor minority groups has been recommended (Jeste et al., Am. J. Public Health, 2009). In Australia, Monash University has a successful Alumni-Student Mentoring Program while the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute encourages informal, ‘organic’ interactions through annual poster symposia, regular seminars and social events.

Is mentoring worth it? The inherent value of mentoring becomes clear when as individuals and as organisations, we place both ourselves and our emerging scientific leaders in the best position to thrive and excel in education, research and innovation, to benefit Australia’s future health and economy.

About the authors:

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!