It Takes a Community to Mentor a Scientist

Summary: Mentors have crucial roles in supporting the development of young scientists, but one mentor may not be enough. Previously I wrote that It takes a community to raise a scientist, here I elaborate on the roles of mentors.

One mentor to rule them all? Nope.

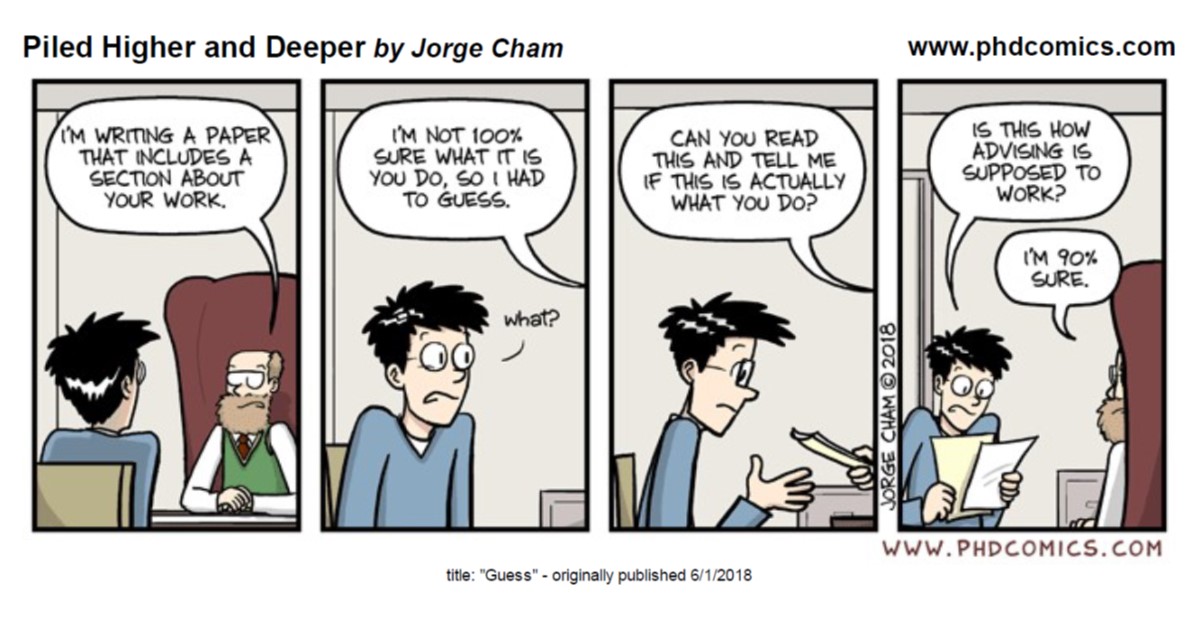

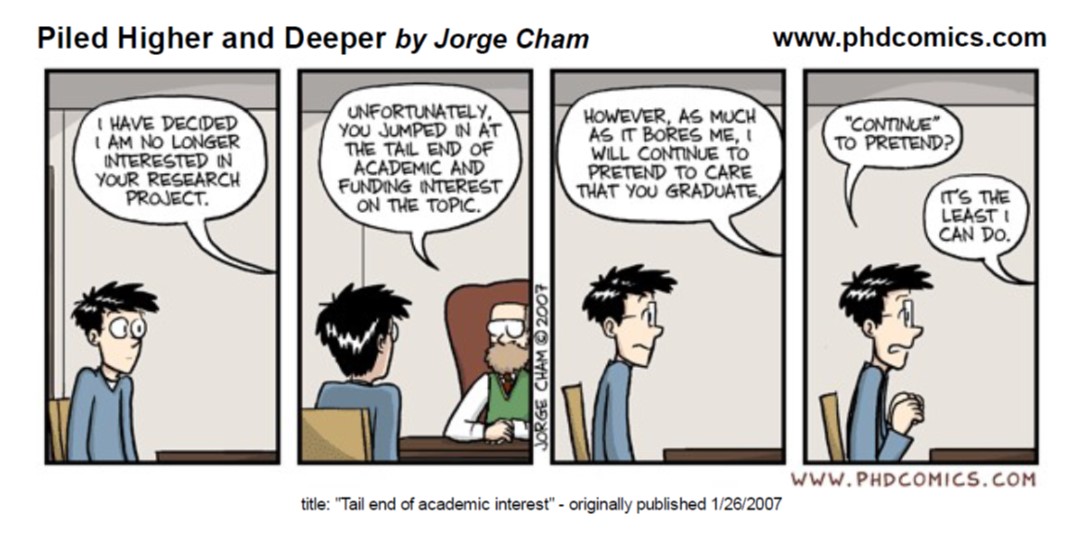

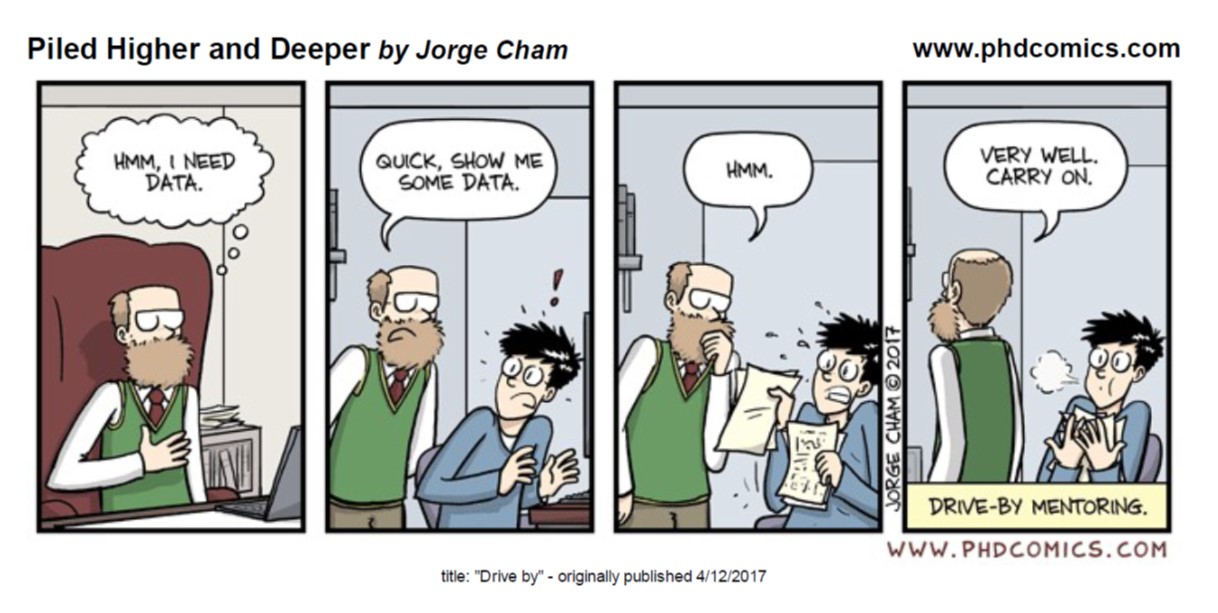

As scientists progress through their careers, their mentoring responsibilities grow, but this is usually accompanied by little or no formal training. As a consequence, the mentoring received by early-career scientists is quite variable. Many don’t even know what to expect from their research supervisor in terms of mentoring. In their 2007 Guide for Mentors, Nature collated statements from individuals who nominated their mentors for awards. Collectively these give a pretty nice overview of what an ideal mentor should offer. Does anyone have all the attributes of a great mentor? Probably not, but it’s a nice goal to aspire to. What about at the other end, the bad or absentee mentor? Unfortunately, these are all too common, and it’s easy to find examples of bad mentoring, from neglect to abuse (please report abusive treatments to university or institutional administrators). Although it’s nearly impossible to enforce good mentoring, some efforts are being made through the NSF’s requirement that each grant that includes funding for postdocs also includes a Postdoctoral Researcher Mentoring Plan.

If you’re lucky enough to have a brilliant mentor, good on you, but for everyone else there is a lot you can do to make up for what you’re missing. Being aware of the importance of getting help to support all aspects of your professional development is a good first step, as is recognizing that it takes many mentors to nuture a scientist.

The many kinds of mentor

It’s unreasonable to expect one mentor to fulfil all of our mentoring needs; rather, we should consider developing a mentoring network. Here are some of the roles a mentor can fill. Think about who helps you in the following ways. If you have gaps, you may find you need to build up your mentoring network!

The sage – This is the person who has broad and deep knowledge of your discipline, and is one of the roles that is most often filled by your research supervisor. After all, you joined their research group to learn from them. However, you should strive to develop relationships with other “sages” to diversify your perspective and broaden your pool of ready knowledge.

The cheerleader – Good news needs to be shared and recognized! Who do you turn to first when your grant is funded or paper is accepted?

The good listener – Bad news also needs to be shared, although not always so publicly. Rejection is part of an academic’s job, but it never is easy. Who is always there when you need a shoulder to cry on, or who will let you express your anger and frustration in confidence?

The connector – Some people are just in the know. They know when an important paper has come out, where the job openings are, who can provide you with a needed reagent, and where to find obscure funding sources. Even when they don’t know, they can put you in touch with someone who does. Increasingly, this role is broadly distributed through social networks and the “hive mind” – Twitter and Plantae.org are increasingly the go-to places to get all of your questions answered and keep up with the latest news.

The editor – Everyone needs feedback on their written work. You should develop a network that you can draw on for feedback at both early and late stages of your writing projects. Early stages require expert knowledge to ensure that you’ve included suitable background material and are interpreting your results appropriately, whereas later stages can focus on readability and grammar. It can be helpful to identify writing buddies who you swap editing tasks with.

The bankroller – Another role primarily assumed by your research supervisor is that of the bankroller. Even if you have your own fellowship, much of the infrastructure and supplies that keep the lab running are there due to the ceaseless grant writing efforts of your supervisor. Be sure to consult the bankroller for guidance when writing your own grants and planning budgets. Grant management is a skill that can be difficult to master, so be pro-active in your quest to learn.

The career coach – You’ve heard that your chances of following your research supervisor into a PI position are slim, but what else can you do? It turns out that having a PhD opens a lot of doors, but it’s not always easy to find those doors. Anyone seriously considering or even just exploring research-complementary careers will benefit from developing a wide network of people in different roles. The more contacts you have, the more you’ll know about different options and the more opportunities you’ll have to ask questions. Conferences are fantastic places to expand your networks – check the schedule for career workshops and career chats. As an example, the Plant Biology 2018 conference has lunchtime workshops and chats on topics that span the breadth of career options.

The life coach – A scientific career isn’t just a job, it’s a lifestyle. One of the biggest challenges we all face is how to juggle our commitment to our science with other interests and responsibilities. Informal networks are invaluable ways to get advice on moving or parenting, and inspiration and motivation for keeping up with your hobbies and fitness goals. The Taproot Podcast, hosted by plant scientists Ivan Baxter and Liz Haswell, has addressed many of these and other challenges.

I particularly like this resource from the Earth Science Women’s Network, which highlights the many types of mentors we all need, and this post that provides suggestions for how you can fill in any gaps in your mentor network.

Advice from my experiences as mentee and mentor

When I was a 19-year old undergraduate, I was offered two research internships, one in the large, busy and intense lab of a future Nobel Laureate, and the other in a much more laid-back lab of a respected but less influential scientist. After much anguish, I chose the smaller lab, and it was one of the best decisions I’ve made. I spent most of the next year and a half in the lab, getting extensive advice and support from the handful of postdocs and graduate students. They helped me learn how to present my data and advised me as I made the important decision about which graduate school to attend. When choosing your next position, don’t overlook the importance of the mentoring you will receive. Prestige matters, but you might benefit even more from an environment that will support you fully.

I have benefitted from several excellent mentors, but the most important and influential guided me through tenure and into my full professorship, and has remained an important colleague. One of the most valuable lessons I learned is the importance of truly listening to your mentees. Find out what they want and need from you – every mentee is different. Taking the time to get to know your mentees will make your job more rewarding and maximize the effectiveness of the time you spend together. Mentors: Talk less, listen more.

My mentees have spanned from hugely talented, dedicated and hardworking, to not-sure-why-they’re here. As much as I have tried to be an effective mentor to all, there is no doubt that I give more to those who put in more effort. As an example, I worked for three years with a student who was good but not great, but who really wanted to do better, particularly in his writing. Because he was so keen to learn, we ended up spending many hours together, going over his texts word-by-word, so he could learn to assess and self-edit his own work. Mentors want to feel that their time and effort are well-spent. Mentees who show a commitment to growing are more rewarding to mentor, and will probably get more benefit from their interactions.

“Broadcast” requests for easy-to-find information and non-specific position inquiries don’t work. Most scientists regularly get email and social media messages sort of vaguely asking for help, advice or opportunities. “Please send me something about ….” is one I get often, and even though I no longer run a research lab I still get “I’m looking for a postdoc, my CV is attached” queries. I, like most others, can’t answer every vague query I get. If you want advice or help, make your query is clearly specific to those you are asking; for example these are the sorts of questions I will find time to respond to, “Hi Mary, I’m considering moving into scientific publishing after my postdoc, could we find a time where I could ask you a few questions about your career track”, or “I’m really interested in science communication, do you recommend any courses or programs to help me get started”. When asking for help or advice, make sure your questions are specific and relevant.

Conclusion: Mentoring is a crucial part of scientific training. Both mentors and mentees can make efforts to maximize the benefits of this interaction. Good mentoring can lead to better productivity, happy students and postdocs, and lifelong friendships.

Further Resources:

Nature’s Guide for Mentors See also Great mentoring is key for the next generation of scientists

Top 10 tips for mentors http://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2010/10/top-10-tips-mentors

How to choose a good mentor http://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2010/10/top-10-tips-mentors

Needed: Flexible Mentors in Science https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2017/05/01/advice-how-research-scientists-can-best-mentor-those-who-work-their-labs-essay

Reaching gender equity in science: The importance of role models and mentors

Montgomery, B. (2017) Mapping a Mentoring Roadmap and Developing a Supportive Network for Strategic Career Advancement. SAGE Open.

Ten types of PhD supervisor relationships – which is yours? The Conversation

A mentor’s acid test. W. Larry Kenny. Nature Careers Column. doi:10.1038/nj7654-377a

The PhD journey: how to choose a good supervisor. New Scientist.

Mentoring for scientists eBook from Addgene

Making the Right Moves: A Practical Guide to Scientific Management for Postdocs and New Faculty, Second Edition HHMI – especially Chapter 5: Mentoring and Being Mentored

MentorNet – MentorNet is a social network for mentoring open to any STEM student in the U.S. STEM students are mentored by professionals working in STEM fields.