Diverse plants, diversity in botany

Guest post by Paul Sokoloff, Senior Research Assistant, Botany, Canadian Museum of Nature

Astragalus, the milkvetch genus, is a massive group of plants in the pea family that has diversified into over 3000 species, which can be found in various habitats across the northern hemisphere. Its also a genus with a surprising queer history. When I was offered an M.Sc. position studying a rare Astragalus species back in my home province of Newfoundland and Labrador, my initial work looking over all the relevant pressed plants and scientific publications kept bringing up the name of a self-taught English botanist who – literally- wrote the book on Astragalus: Rupert Barneby. Here was a person who came to the United States following his passion for plants, and found himself a partner, Dwight Ripley, along the way. Together, they created lives of adventure studying the plants Rupert was so passionate about. I often wish I could have met Rupert, and I am very grateful to have started my career by working on a plant group best known by another gay scientist.

Elegant milkvetch (Astragalus eucosmus) growing wild in Newfoundland and Labrador. Credit: Paul Sokoloff

I started my current job as a botanist at the Canadian Museum of Nature shortly after completing my M.Sc.; about a month after I handed in the final version of my thesis, I boarded a plane bound for Edmonton, and then a smaller plane, and then an even smaller plane, until I landed on the hummocky tundra of Victoria Island in the western Canadian Arctic. There, I spent a month working with the museum’s botany research team documenting the plant biodiversity of this corner of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. At the end of the field season, when we boarded a southbound plane to Yellowknife, two things occurred to me – firstly, how strange the night looked after a month in the midnight sun, and secondly, that I hoped I would soon have another opportunity to work in the north.

/preview.png)

Paul Sokoloff collecting plants in Resolute, Nunavut. Credit: Troy McMullin

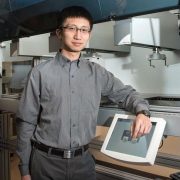

Since then, I have had the privilege of joining 9 field trips across the Canadian Arctic, working with our team to document the flora of this rapidly changing ecosystems. I’ve learned a lot about both the plants that grow above the treeline and a lot about Inuit Nunangat – the Inuit homeland comprised of four regions across the Canadian Arctic. And though my field seasons often mean that I’ve spent many of my summers away from home (July is peak flower-collecting time on the tundra), I’m grateful to have a loving and supportive husband who, as another biologist, is super understanding of the things I do for botany.

Botanists don’t often wear ties, so Dave (left) still has to tie mine for me, like on the day we got married. Credit: Derrick Rice

David and I met back when I was doing my undergraduate degree at Carleton University in Ottawa. We started dating not long after I joined the lab he was conducting his own M.Sc. research in, and got married in a ceremony with many fellow scientists in attendance. Marriage to another scientist means that I come home to a partner who can instantly relate to a lot of the pressures we face in academia, but also has unique challenges. For instance, I had to promise I wouldn’t get grumpy at him if I disagreed with comments he would make on one of my papers (which of course I had asked him to review). And I do have to make an effort to take a few photos of him while on vacation, in addition to countless flower shots I accumulate. In all though, we have a strong partnership that has been strengthened by the support we have received in our respective professional lives. This is a true privilege; I am fortunate enough to be in a situation where I am safe and comfortable enough to be out at work. So, if you ever meet me in the field or at a conference, and I introduce myself with my pronouns, or pre-emptively start talking about my husband, that’s my way of working to cultivate an atmosphere where present and future scientists can comfortably be their authentic selves in their professional lives.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!