The mysterious Pilostyles is a plant within a plant

The Conversation/Wikipedia

Steve Wylie; Jen Mccomb, and Kevin Thiele, University of Western Australia

In 1946, forestry officer Charles Hamilton found something unusual on a shrubby native pea plant growing in Mundaring, near Perth. The pea had strange knobs on its stems, which looked like odd (and very un-pea-like) flowers.

When he showed these to government botanist Charles Gardner, Gardner initially dismissed them as “galls” (the plant equivalent of warts). However, a closer look quickly changed the story.

Read more:

Welcome to Beating Around the Bush, wherein we yell about plants

Gardner realised he was holding a specimen of one of the world’s most extraordinary flowering plants. In 1948, he described it as Pilostyles hamiltonii.

Botanical Aliens

To get a sense of Gardner’s initial dismissal and later fascination, we need to describe Pilostyles. Most plants have a familiar structure of roots, stems, leaves and flowers, and grow in the ground. But a few plants abandon these to become parasites.

The strikingly beautiful Western Australian Christmas tree (Nuytsia floribunda), for example, looks like a normal tree, but it has specialist root structures that tap into the roots of other plants, stealing a free meal from them.

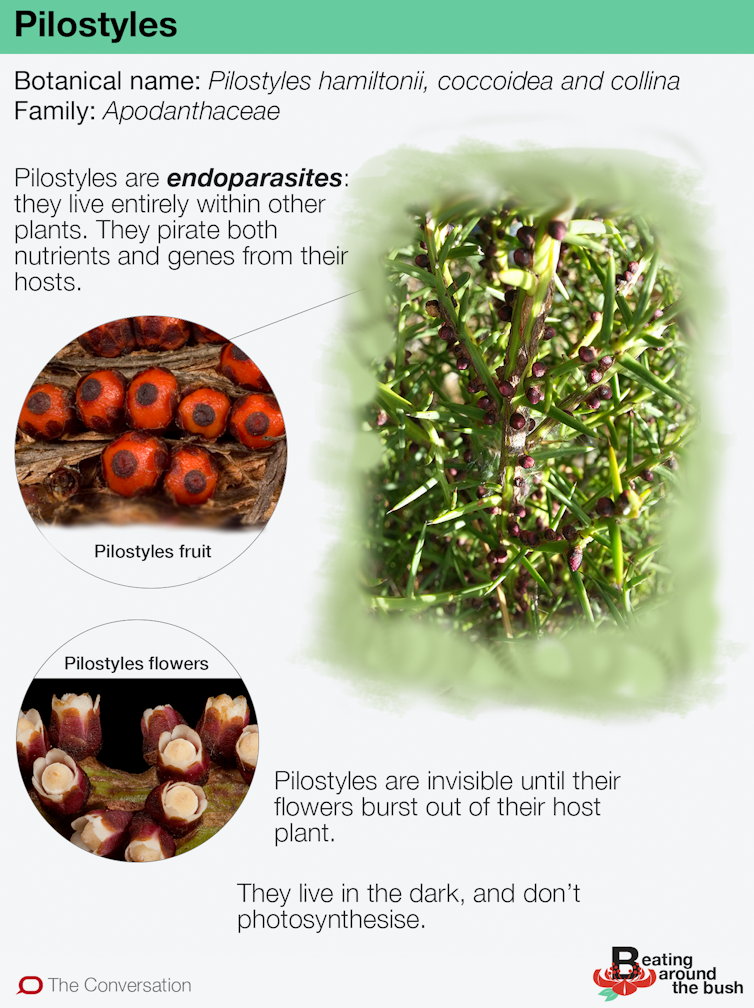

Pilostyles has taken parasitism to another level as an “endoparasite”: it lives inside its host. Unlike almost all other plants, Pilostyles has abandoned stems, leaves and roots. When not flowering, it lives inside its host, as pale threads of cells within the host’s roots and stems, from which it acquires all its nutrients.

Only when flowering is Pilostyles visible externally, the flowers erupting from the stems of its host like a weird botanical Alien.

Three species of Pilostyles occur in Australia, all of them in Western Australia. Each has a specific host. Pilostyles hamiltonii only grows in plants in the genus Daviesia, P. collina in the poison-pea genus Gastrolobium and P. coccoidea – described only a few years ago – in Jacksonia.

Another seven species occur outside Australia, and they also infect shrubby relatives of peas.

Pilostyles flowers are about the size of a match head. They appear on stems after its host has finished its own flowering. Thus, the host plant seems to flower twice in a year, but with completely different flowers.

Curious creatures

Much mystery surrounds Pilostyles. Unlike its host plant, Pilostyles plants are either male or female, and the two sexes rarely, if ever, colonise the same host plant. They seem to be able to recognise a host that is already occupied by another Pilostyles plant. The pollen from a male flower must find its way to a female flower located on another host plant.

Read more:

Can trees really change sex?

Although various insect species have been seen feeding on their flowers, it is uncertain which are effective pollinators and if Pilostyles has specialist pollinators.

Its fruit rots quickly when it falls to the ground. The tiny seeds are less than 1mm long, and each has an embryo of only eight cells and a very small amount of stored food. How the seeds are distributed, and how they recognise their host species amongst all the other plant species growing nearby is unknown. Other parasitic plants recognise root exudations from their hosts, but this is not proven for Pilostyles.

Because Pilostyles lives in the dark and doesn’t photosynthesise, it has no apparent need for chloroplasts, the cell structures that synthesise sugars from carbon dioxide, water and sunlight and give other plants their green colouration.

Chloroplast have their own genomes because they are thought to originate from free-living cyanobacteria that themselves parasitised other cells to become the first plants.

Surprisingly, Pilostyles still retains remnant choloroplasts with tiny genomes that contain only five or six active genes. These are the smallest chloroplast genomes ever described. In comparison, the chloroplast genome of wheat encodes about 230 genes.

Several genes in the Pilostyles nuclear genome closely resemble genes of its host, suggestive that the parasite is not only pirating nutrients from its host, but also its genes. This phenomenon is called horizontal gene transfer, and it is relatively common amongst plants that are parasites.

Pilostyles was once regarded as being closely related to an equally bizarre plant, the famous giant-flowered Rafflesia from South-east Asia, which grows as an endoparasite inside a tropical vine. (Also known as the “corpse flower”, the only visible part is the enormous flower that smells like rotting meat.)

At that time, taxonomists classified plants according to overall resemblance, and Pilostyles and Rafflesia resemble one another – in both being endoparasites. However, DNA extracted from Pilostyles flowers shows that resemblance is deceiving. Pilostyles is, in fact, more closely related to pumpkins than it is to Rafflesia.

The ancestor of today’s Pilostyles rejected life as a green plant living in sunlight, instead worming its way into the body of another plant. Over evolutionary time, Pilostyles has survived ice ages and tectonic plate movements and now exists as ten described species living on five continents. The mysterious Pilostyles reminds us of the incredible tenacity and adaptability of life.

![]()

Read more:

Mountain ash has a regal presence: the tallest flowering plant in the world

Steve Wylie, Molecular virology, virus ecology and evolution, metagenomics, symbiosis; Jen Mccomb, Emeritus professor, and Kevin Thiele, Adjunct Senior Lecturer, University of Western Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.