Lack of Minoritized Inclusion in STEM: Beyond Mentoring to Meaningful Change

An article by Rebecca Roston, Lesley Murphy, Imara Perera, Ebony McGee.

Dr. Ebony McGee’s powerful address at the 2024 Plant Biology meeting ignited a critical conversation about structural racism in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics). Her talk was co-sponsored by the Women in Plant Biology and Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion committees with the encouragement of ASPB President Leeann Thornton. Inspired by her insights and the urgency to address these issues, we aim to extend this dialogue and advocate for systemic change.

Why advocate for greater inclusion in STEM for underrepresented racially minoritized people? The answer is clear: diversity drives innovation. Companies boasting diverse teams are 35% more likely to outperform industry averages (Rock & Grant, 2016). Moreover, underrepresented minoritized people in STEM have fundamental principles guiding behavior and action thriving toward justice, especially racial justice, and rectifying racial inequities through the employment of one’s STEM abilities– termed Equity Ethics (McGee, 2020a; McGee et al., 2023). This intrinsic motivation, coupled with the proven benefits of diversity, underscores the imperative for fostering a more inclusive STEM ecosystem.

In recent years, discussions about diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) have gained momentum across various fields, including STEM. Yet, despite these efforts, the underrepresentation of the minoritized persists, and the experiences of those who do make it through the door reveal significant challenges (McGee, 2020b; White et al., 2023). In this post, we explore the deep-seated consequences of structural racism in STEM, examine the impact on underrepresented minorities, critique current interventions, and call for systemic change.

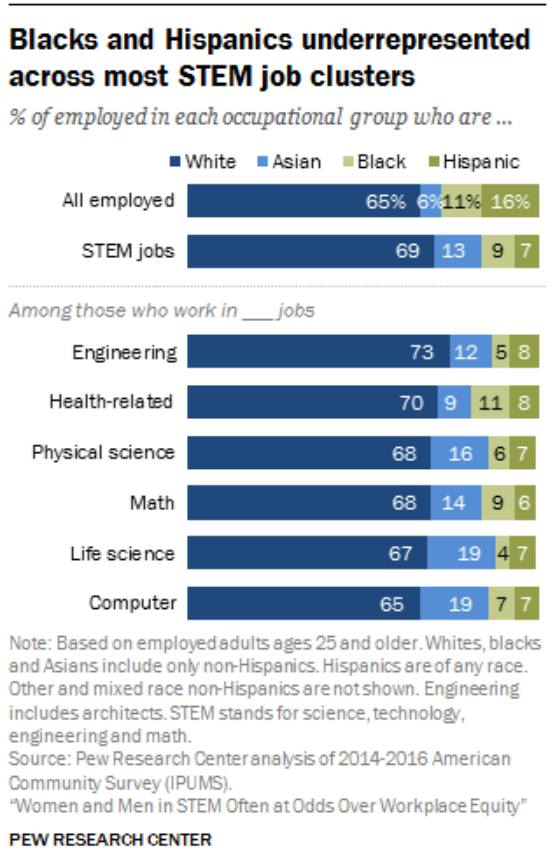

Underrepresentation in STEM

The STEM fields have long struggled with a lack of diversity. Data consistently shows that Black, Latino, and Indigenous individuals are underrepresented in STEM education and careers. As one example, Pew Research Center’s 2016 survey showed that while the demographics of the general population are increasingly diverse, the representation of minority groups in STEM remains disproportionately low regardless of the education level considered. This underrepresentation is not merely a numerical discrepancy but is indicative of broader systemic issues that marginalize these groups (Haverroth et al., 2024).

The Experience of the Underrepresented and Racially Minoritized

For the underrepresented and racially minoritized in STEM, the journey is fraught with unique challenges. Black and brown students across STEM often face a heightened sense of “imposter syndrome,” which is more accurately described as a reaction to structural racism rather than an individual psychological issue (McGee, 2020a; NAS, 2023; White et al., 2023). This phenomenon occurs because the dominant discourse around imposter syndrome fails to acknowledge the underlying racial biases and systemic inequities that contribute to these feelings of inadequacy.

Furthermore, underrepresented racially minoritized students in STEM frequently experience elevated stress due to the racialized and oppressive environments of their academic and professional settings. Research indicates that these students often engage in “John Henryism”—a strategy of working harder, to the detriment of their health and relationships, to overcome adversity (McGee, 2020a; McGee, 2020b). Often perceived as resilience, John Henryism can result in academic success, though it can take a significant physical, psychological, and emotional toll.

The “John Henryism” can be amplified further at the faculty or professional levels where faculty of color are severely underrepresented. Only 6% of faculty at postsecondary institutions are Black, and only 5% Hispanic, while their collective population in the US is approximately 32% (Davis and Fry, 2019). As a result of historical racialized oppression intersecting with their unusual and often alone status, these faculty commonly experience microaggressions and expectations of invisible labor (McGee, 2020a), frequently coping through a combination of overwork and dedication (Mickles-Burns, 2024). The result of the increased expectations placed on faculty of color, whether self-imposed or coming from administration or peers, is low retention (McGee, 2020a).

Resilience is Not a Healthy Coping Mechanism

The emphasis on resilience as a coping mechanism for underrepresented minoritized individuals in STEM is problematic. While resilience is often praised as a virtue, it should not be seen as a solution to structural issues (McGee, 2020a; McGee, 2020b; NAS, 2023). Emphasizing resilience under conditions of structural racism, which features harassment, microaggressions, and high service loads can lead to harmful consequences, including burnout and psychological distress. The focus should shift from expecting individuals to adapt to a flawed system to addressing and dismantling the systemic barriers that perpetuate inequities.

Call to Action

Recognize Structural Racism: It is crucial to acknowledge that structural racism exists within STEM institutions and industries. This recognition is the first step towards meaningful change. It involves understanding how institutional policies, norms, and funding disparities perpetuate inequities. This reality has been recognized by multiple calls to action from academic societies (American College of Surgeons, 2020; Bowden and Buie, 2021; Ham, 2020; NAS, 2023).

Seek Training in Cultural Awareness: Institutions must invest in training programs that foster cultural awareness and inclusive mentoring (McGee, 2020a; NAS, 2023). This training should not only address how to mentor underrepresented minority students effectively but also how to create and maintain inclusive and supportive environments; examples include the Root and Shoot mentoring program and the Culturally Aware Mentoring program.

Institutional Changes: Beyond mentoring programs, which often fall short in addressing systemic issues, STEM institutions need to undertake active, institutional changes. This includes equitable funding practices, revising evaluation systems to eliminate bias, and fostering diverse leadership. Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) play a vital role in advancing diversity in STEM but need more support to address the systemic disparities they face (McGee 2020a; McGee, 2020b; McGee, 2023; NAS, 2023).

Promote Equity Ethics: Adopting an Equity Ethics approach is essential. This perspective emphasizes a commitment and action-oriented approach to racial justice and the use of STEM resources and positions to address and mitigate structural oppression. Institutions should strive to integrate these ethics into their core values and operational practices. You can help advocate for this at the departmental level, a level which is often seen as the greatest impediment to meaningful change (McGee et al., 2023; NAS Press, 2005; Mitchneck et al., 2016).

In conclusion, addressing the underrepresentation of minoritized individuals in STEM requires more than just surface-level interventions or mentoring training. It demands a thorough examination and transformation of the structural racism embedded in these fields. By recognizing and acting upon these issues, we can move towards a more equitable and inclusive STEM landscape where all individuals have the opportunity to thrive.

Afterward: Dr. McGee’s talk sparked a passionate discussion among attendees about the pervasive structural racism in STEM fields, highlighting the need for ongoing dialogue and action. As Anne-Marie Pullen noted, “Dr. McGee did a fantastic job of providing a very concise criticism of the ways in which our institutions and professional culture undercut the achievements of people of color and provided clear ways to address these issues.” Miguel Vega-Sanchez echoed this sentiment, appreciating Dr. McGee’s ability to connect her personal experiences to the broader challenges all faced. Bethany Mostert’s reflection on the seminar underscored the importance of confronting the harsh realities faced by minoritized individuals in academia. “I was very grateful to our speaker and to all the participants for not shying away from the darker sides to this conversation because clearly, it is a conversation that still needs to be had and heard.” In summary, Dr. McGee’s seminar cemented the need for change, reminding attendees of the urgent and persistent need to address systemic racism in STEM.

For those interested in delving deeper into these critical topics, Dr. McGee’s book, Black, Brown, Bruised: How Racialized STEM Education Stifles Innovation (2020), offers an in-depth exploration of these issues and is an invaluable resource for understanding and addressing systemic inequities in STEM.

Left to right: Lesley Murphy, Ebony McGee, and Mary Fernandez at Plant Biology 2024

References

American College of Surgeons Board of Regents and American College of Surgeons Committee on Ethics (2020) American College of Surgeons Call to Action on Racism as a Public Health Crisis: An Ethical Imperative. Online, accessed 8/15/2024. https://www.facs.org/about-acs/responses/racism-as-a-public-health-crisis/

Bowden, A.K., Buie, C.R. (2021) Anti-Black racism in academia and what you can do about it. Nat Rev Mater 6, 760–761. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-021-00361-5

Davis L., Fry R. (2019) College Faculty Have Become More Racially and Ethnically Diverse, but Remain Far Less So than Students. Pew Research Center. https://pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/07/31/us-college-faculty-Student-diversity/

Ham, B. (2020). AAAS drafts plan to address systemic racism in sciences. Science, 370(6516), 541-542. doi:doi:10.1126/science.370.6516.541

Haverroth et. al (2024) The Black American experience: Answering the global challenge of broadening participation in STEM/agriculture. The Plant Cell, 36(4) 807-811 https://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koae002

McGee, E. O. (2020a). Black, Brown, Bruised: How Racialized STEM Education Stifles Innovation. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press.

McGee, E. O. (2020b). Interrogating Structural Racism in STEM Higher Education. Educational Researcher, 49(9), 633-644. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20972718

McGee, E. O. et. al (2023) Accelerating Racial Activism in STEM Higher Education by Institutionalizing Equity Ethics (2023) Teachers College Record Vol. 125(9) 108–139

Mitchneck, B., Smith, J. L., & Latimer, M. (2016). A recipe for change: Creating a more inclusive academy. Science, 352(6282), 148-149.

Mickles-Burns, L. (2024). Voices of Black Faculty at Predominantly White Institutions: Coping Strategies and Institutional Interventions. Journal of Applied Social Science, 18(1), 136-153.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2023. Psychological Factors That Contribute to the Dearth of Black Students in Science, Engineering, and Medicine: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26691

National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine. (2005) Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research. NAS Press. p. 73, 74. https://doi.org/10.17226/11153

Funk, C., & Parker, K. (2018) “Women and Men in STEM Often at Odds Over Workplace Equity” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/01/09/women-and-men-in-stem-often-at-odds-over-workplace-equity/

Rock D. and Grant H. (2016) “Why Diverse Teams are Smarter” Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter

White D. T. et. al (2023) How do Black engineering and computing doctoral students analyze and appraise their (depleted) STEM diversity programming? Front. Educ. 8:1062556. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1062556