Plant Science Research Weekly: January 24, 2025

Review. Unraveling plant-microbe interaction dynamics: Insights from the Tripartite Symbiosis Model

Plants naturally interact with a diverse array of microorganisms, which influence their fitness in various ways. However, understanding these plant-microbe interactions and applying the knowledge in real-world agricultural systems has been challenging. Most experimental research focuses on bipartite systems, where a single plant species is paired with one microbial species. This oversimplification fails to capture the complexity of natural ecosystems, where plants typically engage with multiple microorganisms simultaneously. One promising model for exploring these complex interactions is the tripartite symbiosis between legumes, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), and nitrogen-fixing rhizobia. This tripartite system provides valuable insights into the intricate relationships that govern plant-microbe dynamics and brings researchers closer to understanding how these multifactorial interactions shape plant health and productivity. In their review, Gorgia and Tsikou examine current knowledge and challenges associated with this system. They highlight that the effects of dual inoculation with both AMF and rhizobia cannot be predicted by simply adding the individual contributions of each microorganism, as indicated by multi-omics analyses. Moreover, factors such as partner compatibility, nutrient availability, environmental conditions, plant autoregulation, and the interactions between microbes inside (intraradical) and outside (extraradical) the root tissue all play critical roles. Together, these factors shape the rhizosphere community, influence root morphology, and ultimately affect the competitive dynamics of plants. Although the tripartite system remains relatively simple, it serves as a foundational model for studying more complex multispecies interactions that could have important applications in agriculture, particularly in enhancing crop productivity and sustainability. (Summary by Ching Chan @ntnuchanlab) Plant, Cell & Environment 10.1111/pce.15341

Plants naturally interact with a diverse array of microorganisms, which influence their fitness in various ways. However, understanding these plant-microbe interactions and applying the knowledge in real-world agricultural systems has been challenging. Most experimental research focuses on bipartite systems, where a single plant species is paired with one microbial species. This oversimplification fails to capture the complexity of natural ecosystems, where plants typically engage with multiple microorganisms simultaneously. One promising model for exploring these complex interactions is the tripartite symbiosis between legumes, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), and nitrogen-fixing rhizobia. This tripartite system provides valuable insights into the intricate relationships that govern plant-microbe dynamics and brings researchers closer to understanding how these multifactorial interactions shape plant health and productivity. In their review, Gorgia and Tsikou examine current knowledge and challenges associated with this system. They highlight that the effects of dual inoculation with both AMF and rhizobia cannot be predicted by simply adding the individual contributions of each microorganism, as indicated by multi-omics analyses. Moreover, factors such as partner compatibility, nutrient availability, environmental conditions, plant autoregulation, and the interactions between microbes inside (intraradical) and outside (extraradical) the root tissue all play critical roles. Together, these factors shape the rhizosphere community, influence root morphology, and ultimately affect the competitive dynamics of plants. Although the tripartite system remains relatively simple, it serves as a foundational model for studying more complex multispecies interactions that could have important applications in agriculture, particularly in enhancing crop productivity and sustainability. (Summary by Ching Chan @ntnuchanlab) Plant, Cell & Environment 10.1111/pce.15341

Review: High-yield farming is essential to slow biodiversity loss

It’s 2025, and although we live in a world saturated with information, is increasingly difficult to sort fact from propaganda or fiction. This is true in all arenas, including plant science. Calls for strategies to improve crop yields are sometimes met with criticisms that higher yielding crops would only serve “big ag” or further harm biodiversity. That’s why I enjoyed reading this well-researched but accessible review article by Bamford et al. that lays out the need for high-yield farming to “bend the curve” of biodiversity loss, part of a special issue honoring the legacy of biodiversity researcher Georgina Mace. (You can find the rest of this special issue here https://royalsocietypublishing.org/toc/rstb/2025/380/1917). The authors address several issues, including the fact that feeding the human population “remains the pre-eminent threat to wild nature” and that so-called “land sharing” strategies (in which wildlife cohabitates with agriculture) don’t work very well. Therefore, they call for “land sparing”, which means keeping farming’s footprint as small as possible, through increasing yields. These yield increases can come about through crop improvement but also through making sure farmers have access to and are using best practices, such as integrated pest management and drip irrigation. The final paragraph of their article sums up the social challenges eloquently, have a look. (Summary by Mary Williams @PlantTeaching.bksy.social @PlantTeaching) Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 10.1098/rstb.2023.0216

It’s 2025, and although we live in a world saturated with information, is increasingly difficult to sort fact from propaganda or fiction. This is true in all arenas, including plant science. Calls for strategies to improve crop yields are sometimes met with criticisms that higher yielding crops would only serve “big ag” or further harm biodiversity. That’s why I enjoyed reading this well-researched but accessible review article by Bamford et al. that lays out the need for high-yield farming to “bend the curve” of biodiversity loss, part of a special issue honoring the legacy of biodiversity researcher Georgina Mace. (You can find the rest of this special issue here https://royalsocietypublishing.org/toc/rstb/2025/380/1917). The authors address several issues, including the fact that feeding the human population “remains the pre-eminent threat to wild nature” and that so-called “land sharing” strategies (in which wildlife cohabitates with agriculture) don’t work very well. Therefore, they call for “land sparing”, which means keeping farming’s footprint as small as possible, through increasing yields. These yield increases can come about through crop improvement but also through making sure farmers have access to and are using best practices, such as integrated pest management and drip irrigation. The final paragraph of their article sums up the social challenges eloquently, have a look. (Summary by Mary Williams @PlantTeaching.bksy.social @PlantTeaching) Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 10.1098/rstb.2023.0216

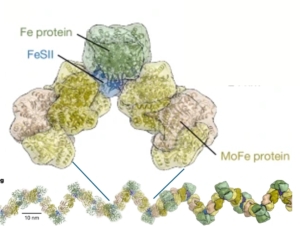

How nitrogenase stays active

One of the great dilemmas of science is the fact that nitrogen gas, though very abundant in the atmosphere, is limiting for most forms of life. Of course, this lack of availability is because N2 gas has an extremely strong triple bond holding the two nitrogen atoms together; it’s so strong that N2 gas is considered “inert” and foods are often packaged in N2 to prolong shelf life. Fortunately, some prokaryotes produce an enzyme, nitrogenase, that can break this triple bond to produce ammonium (NH4+), which can be taken up and used by other organisms. However, this essential enzyme has an Achilles heel, which is that it is rapidly inactivated by oxygen. Fortunately, many nitrogen-fixing organisms produce a protein called FeSII (also known as Shethna protein II) that protects nitrogenase from oxygen, in a mechanism that has just been revealed in two back-to-back articles by Franke et al. and Narehood et al. Nitrogenase is made up of two protein complexes [iron protein (FeP) and molybdenum–iron protein (MoFeP)] containing several metal cofactors. The authors used cryo-EM to image this complex in the presence and absence of oxygen, and they found that in the presence of oxygen, FeSII reversibly binds to these metal-containing regions, protecting them from oxidative damage. Interestingly, the authors also found that the single protected structures can multimerize further into higher-order filaments. Not only is this beautiful work, but it also provides key insights that can one day be used to engineer plants that can fix nitrogen on their own. (Summary by Mary Williams @PlantTeaching.bksy.social @PlantTeaching) Nature10.1038/s41586-024-08355-3 and 10.1038/s41586-024-08311-1.

One of the great dilemmas of science is the fact that nitrogen gas, though very abundant in the atmosphere, is limiting for most forms of life. Of course, this lack of availability is because N2 gas has an extremely strong triple bond holding the two nitrogen atoms together; it’s so strong that N2 gas is considered “inert” and foods are often packaged in N2 to prolong shelf life. Fortunately, some prokaryotes produce an enzyme, nitrogenase, that can break this triple bond to produce ammonium (NH4+), which can be taken up and used by other organisms. However, this essential enzyme has an Achilles heel, which is that it is rapidly inactivated by oxygen. Fortunately, many nitrogen-fixing organisms produce a protein called FeSII (also known as Shethna protein II) that protects nitrogenase from oxygen, in a mechanism that has just been revealed in two back-to-back articles by Franke et al. and Narehood et al. Nitrogenase is made up of two protein complexes [iron protein (FeP) and molybdenum–iron protein (MoFeP)] containing several metal cofactors. The authors used cryo-EM to image this complex in the presence and absence of oxygen, and they found that in the presence of oxygen, FeSII reversibly binds to these metal-containing regions, protecting them from oxidative damage. Interestingly, the authors also found that the single protected structures can multimerize further into higher-order filaments. Not only is this beautiful work, but it also provides key insights that can one day be used to engineer plants that can fix nitrogen on their own. (Summary by Mary Williams @PlantTeaching.bksy.social @PlantTeaching) Nature10.1038/s41586-024-08355-3 and 10.1038/s41586-024-08311-1.

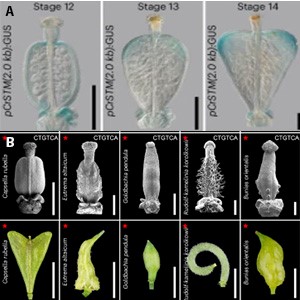

Capsella rubella: My Fruity Valentine

Most shapes in plant organs are pre-determined at the primordial stage and from this point, growth will establish and maintain this shape. Rarely will re-shaping of an organ occur post-organogenesis. However, Hu et al. describe a notable exception in Capsella rubella, a close relative of Arabidopsis thaliana. Capsella’s female reproductive organ, the gynoecium, undergoes a geometric rearrangement where its initially flat, spheroidal structure is re-shaped into a heart-shape upon fertilization. Hu et al. used a complex of technologies from single cell RNA sequencing to whole-organ live cell imaging to piece together the mechanisms underlying re-shaping. At the cellular level, this paper provides evidence that a gradient of differentiation, as well as regional anisotropic growth (different growth in different directions), support the re-shaping of the gynoecium. Molecularly, they identified an important gene supporting this process: SHOOTMERISTEMLESS (CrSTM). CrSTM expression is induced by local auxin signaling. CrSTM then binds a specific region in its own promoter to maintain its expression through an autoregulatory positive feedback loop. Intriguingly, this STM self-binding site is conserved throughout Brassicaceae species which re-shape their gynoecia post-fertilization. Altogether these findings demonstrate the evolutionary significance of STM autoregulation, coordinated cell division, and localized growth in re-shaping. (Summary by Kes Maio @KestrelMaio @kesmaio.bsky.social) Nature Plants 10.1038/s41477-024-01854-1

Most shapes in plant organs are pre-determined at the primordial stage and from this point, growth will establish and maintain this shape. Rarely will re-shaping of an organ occur post-organogenesis. However, Hu et al. describe a notable exception in Capsella rubella, a close relative of Arabidopsis thaliana. Capsella’s female reproductive organ, the gynoecium, undergoes a geometric rearrangement where its initially flat, spheroidal structure is re-shaped into a heart-shape upon fertilization. Hu et al. used a complex of technologies from single cell RNA sequencing to whole-organ live cell imaging to piece together the mechanisms underlying re-shaping. At the cellular level, this paper provides evidence that a gradient of differentiation, as well as regional anisotropic growth (different growth in different directions), support the re-shaping of the gynoecium. Molecularly, they identified an important gene supporting this process: SHOOTMERISTEMLESS (CrSTM). CrSTM expression is induced by local auxin signaling. CrSTM then binds a specific region in its own promoter to maintain its expression through an autoregulatory positive feedback loop. Intriguingly, this STM self-binding site is conserved throughout Brassicaceae species which re-shape their gynoecia post-fertilization. Altogether these findings demonstrate the evolutionary significance of STM autoregulation, coordinated cell division, and localized growth in re-shaping. (Summary by Kes Maio @KestrelMaio @kesmaio.bsky.social) Nature Plants 10.1038/s41477-024-01854-1

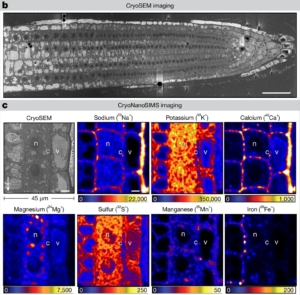

SOS1, salt, and cryo-imaging of subcellular element distribution

For living organisms, proper control of element location is just as important as the control of enzyme location, but harder to study. A new study by Ramakrishna et al. uses an exciting new technology, cryo nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry ion microprobe, to investigate elemental distribution (measured by their major isotopes) in Arabidopsis and rice roots. The images are beautiful, and different elements can be clearly seen localized within different subcellular compartments, including the cytosol, vacuole, and apoplast. Here, the authors investigated the subcellular distribution of sodium (Na+) in root cells. Plant cells are very sensitive to cytosolic sodium levels and use pumps to maintain a low concentration in the cytosol. In wild-type plants in mild salt stress (2.5 mM), sodium is almost entirely found in the apoplast, whereas when the salt concentration is moderate (25mM) the sodium mainly accumulates in the vacuole. The authors also examined mutants of a sodium transporter SOS1 (SODIUM OVERLY SENSITIVE 1). SOS1 was previously shown to be a sodium/proton antiporter localized in the plasma membrane that contributes to sodium export from the cytosol. In these sos1 mutant plants the authors observed a very different pattern of sodium accumulation at moderate salt levels; the salt remained elevated in the apoplast with very little accumulating in the vacuole, indicating a role for SOS1 in moving sodium into the vacuole. This study demonstrates a new role for SOS1, and introduces a powerful new imaging technology. (Summary by Mary Williams @PlantTeaching.bksy.social @PlantTeaching) Nature 10.1038/s41586-024-08403-y

For living organisms, proper control of element location is just as important as the control of enzyme location, but harder to study. A new study by Ramakrishna et al. uses an exciting new technology, cryo nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry ion microprobe, to investigate elemental distribution (measured by their major isotopes) in Arabidopsis and rice roots. The images are beautiful, and different elements can be clearly seen localized within different subcellular compartments, including the cytosol, vacuole, and apoplast. Here, the authors investigated the subcellular distribution of sodium (Na+) in root cells. Plant cells are very sensitive to cytosolic sodium levels and use pumps to maintain a low concentration in the cytosol. In wild-type plants in mild salt stress (2.5 mM), sodium is almost entirely found in the apoplast, whereas when the salt concentration is moderate (25mM) the sodium mainly accumulates in the vacuole. The authors also examined mutants of a sodium transporter SOS1 (SODIUM OVERLY SENSITIVE 1). SOS1 was previously shown to be a sodium/proton antiporter localized in the plasma membrane that contributes to sodium export from the cytosol. In these sos1 mutant plants the authors observed a very different pattern of sodium accumulation at moderate salt levels; the salt remained elevated in the apoplast with very little accumulating in the vacuole, indicating a role for SOS1 in moving sodium into the vacuole. This study demonstrates a new role for SOS1, and introduces a powerful new imaging technology. (Summary by Mary Williams @PlantTeaching.bksy.social @PlantTeaching) Nature 10.1038/s41586-024-08403-y

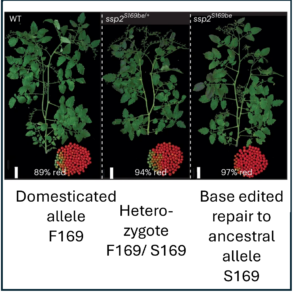

Repairing a detrimental domestication variant improves tomato harvests

Domesticated plants and animals are remarkable human achievements but were achieved with rather blunt instruments. With the benefit of hindsight, we can now see that some of the genes and alleles that passed through the population bottlenecks and artificial selection process are deleterious. Glaus et al. looked at several tomato wild species, land races, and domesticated varieties. They found large numbers of non-synonymous mutations (coding for a different amino acid) and focused on the genes involved in flowering time, the florigen-activation complex. In tomato, the SELF-PRUNING (SP) gene acts as an anti-florigen that suppresses flowering. Another gene, SUPPRESSOR OF SP (SSP), has previously been used to control plant architecture and time of flowering. The authors identified a related gene, SSP2, that shows a deleterious mutation (S to F) in the DNA-binding domain in domesticated tomatoes. Introgressing the ancestral allele from wild tomatoes led to earlier flowering and a more compact inflorescence. The authors subsequently showed that the deleterious mutation interferes with the ability of SSP2 to bind DNA and act as a transcription factor. Next, they used CRISPR/Cas9 base editing to repair this mutation and restore the ancestral allele in domesticated tomato. The resulting plants showed a more compact growth, earlier flowering, and higher proportion of ripe fruit at harvest. This study shows that today’s powerful genomic tools can identify and repair deleterious alleles that are prevalent in domesticated plants and animals, correcting some unintended outcomes of our ancestors. (Summary by Mary Williams @PlantTeaching.bksy.social @PlantTeaching) Nature Genetics 10.1038/s41588-024-02026-9

Domesticated plants and animals are remarkable human achievements but were achieved with rather blunt instruments. With the benefit of hindsight, we can now see that some of the genes and alleles that passed through the population bottlenecks and artificial selection process are deleterious. Glaus et al. looked at several tomato wild species, land races, and domesticated varieties. They found large numbers of non-synonymous mutations (coding for a different amino acid) and focused on the genes involved in flowering time, the florigen-activation complex. In tomato, the SELF-PRUNING (SP) gene acts as an anti-florigen that suppresses flowering. Another gene, SUPPRESSOR OF SP (SSP), has previously been used to control plant architecture and time of flowering. The authors identified a related gene, SSP2, that shows a deleterious mutation (S to F) in the DNA-binding domain in domesticated tomatoes. Introgressing the ancestral allele from wild tomatoes led to earlier flowering and a more compact inflorescence. The authors subsequently showed that the deleterious mutation interferes with the ability of SSP2 to bind DNA and act as a transcription factor. Next, they used CRISPR/Cas9 base editing to repair this mutation and restore the ancestral allele in domesticated tomato. The resulting plants showed a more compact growth, earlier flowering, and higher proportion of ripe fruit at harvest. This study shows that today’s powerful genomic tools can identify and repair deleterious alleles that are prevalent in domesticated plants and animals, correcting some unintended outcomes of our ancestors. (Summary by Mary Williams @PlantTeaching.bksy.social @PlantTeaching) Nature Genetics 10.1038/s41588-024-02026-9

Interconnected memories: How heat stress and bacterial infection shape plant resilience

Memory—a mysterious cognitive process that retains information over time and shapes future interpretations and actions—is not exclusive to animals. In plants, a similar phenomenon occurs where past exposure to environmental stressors is “memorized,” enabling plants to respond more effectively to subsequent challenges. This adaptive capability is exemplified by acquired thermotolerance (ATT) and systemic acquired resistance (SAR), two well-documented cases of plant memory. Fascinatingly, Nishad and colleagues uncovered an unexpected crosstalk between these seemingly distinct processes, revealing how they can prime one another. On one side, bacterial infection enhances plant tolerance to heat stress by promoting the sustained upregulation of heat shock proteins, with effects that persist longer than typical ATT responses. Conversely, heat stress influences SAR in an opposite direction, decreasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and consequently diminishing plant resistance to bacterial pathogens. Moreover, experiments in mutants deficient in heat shock memory regulators demonstrated that SAR is abolished in the absence of these factors, underscoring the pivotal role of heat shock proteins in mediating immune responses. This study highlights the intricate connections between heat stress signaling and plant immunity, offering exciting possibilities for cross-protection strategies. By understanding these interconnected mechanisms, researchers could develop innovative approaches to enhance crop resilience against combined stressors, improving agricultural sustainability in a changing climate. (Summary by Ching Chan @ntnuchanlab) Plant, Cell & Environment 10.1111/pce.15364

Memory—a mysterious cognitive process that retains information over time and shapes future interpretations and actions—is not exclusive to animals. In plants, a similar phenomenon occurs where past exposure to environmental stressors is “memorized,” enabling plants to respond more effectively to subsequent challenges. This adaptive capability is exemplified by acquired thermotolerance (ATT) and systemic acquired resistance (SAR), two well-documented cases of plant memory. Fascinatingly, Nishad and colleagues uncovered an unexpected crosstalk between these seemingly distinct processes, revealing how they can prime one another. On one side, bacterial infection enhances plant tolerance to heat stress by promoting the sustained upregulation of heat shock proteins, with effects that persist longer than typical ATT responses. Conversely, heat stress influences SAR in an opposite direction, decreasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and consequently diminishing plant resistance to bacterial pathogens. Moreover, experiments in mutants deficient in heat shock memory regulators demonstrated that SAR is abolished in the absence of these factors, underscoring the pivotal role of heat shock proteins in mediating immune responses. This study highlights the intricate connections between heat stress signaling and plant immunity, offering exciting possibilities for cross-protection strategies. By understanding these interconnected mechanisms, researchers could develop innovative approaches to enhance crop resilience against combined stressors, improving agricultural sustainability in a changing climate. (Summary by Ching Chan @ntnuchanlab) Plant, Cell & Environment 10.1111/pce.15364

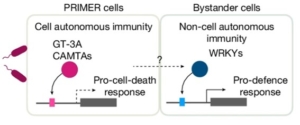

Single cell multiomic analysis of plant immunity reveals PRIMER cells

Single cell mutiomics are radically changing our understanding of pretty much every cellular process. Here, Nobori et al. integrated single-cell transcriptomic, epigenomic and spatial transcriptomic data to investigate plant responses to pathogens. The authors used three different strains of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000; the wild-type (referred to as DC3000) which causes disease, and two avirulent variants, DC3000 AvrRpt2 and AvrRpm1 that produce effectors that trigger the plant immune response. Nuclei were isolated at various times after inoculation for single-nucleus RNA-seq and single-nucleus assay for transposase-accessible chromatin followed by sequencing (snATAC–seq), a method for identifying chromosome regions accessible to transcription factors and likely to indicate active genes. These large datasets revealed a wealth of information, including the fact that a subset of cells act as primary immune responder (PRIMER) cells. These PRIMER cells express a novel transcription factor and are surrounded by “bystander” cells that activate systemic responses. The datasets are publicly available at https://plantpathogenatlas.salk.edu. (Summary by Mary Williams @PlantTeaching.bksy.social @PlantTeaching) Nature 10.1038/s41586-024-08383-z

Single cell mutiomics are radically changing our understanding of pretty much every cellular process. Here, Nobori et al. integrated single-cell transcriptomic, epigenomic and spatial transcriptomic data to investigate plant responses to pathogens. The authors used three different strains of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000; the wild-type (referred to as DC3000) which causes disease, and two avirulent variants, DC3000 AvrRpt2 and AvrRpm1 that produce effectors that trigger the plant immune response. Nuclei were isolated at various times after inoculation for single-nucleus RNA-seq and single-nucleus assay for transposase-accessible chromatin followed by sequencing (snATAC–seq), a method for identifying chromosome regions accessible to transcription factors and likely to indicate active genes. These large datasets revealed a wealth of information, including the fact that a subset of cells act as primary immune responder (PRIMER) cells. These PRIMER cells express a novel transcription factor and are surrounded by “bystander” cells that activate systemic responses. The datasets are publicly available at https://plantpathogenatlas.salk.edu. (Summary by Mary Williams @PlantTeaching.bksy.social @PlantTeaching) Nature 10.1038/s41586-024-08383-z

Dioecious dynamics: How male and female poplars shape microbial networks under stress

Plants actively shape the microbial community in their rhizosphere to optimize nutrient acquisition and enhance resilience against environmental stresses. Interestingly, in dioecious plants, male and female individuals play distinct ecological roles and evolve different environmental adaptability. For instance, female poplar trees tend to allocate more resources to vegetative growth and reproduction, whereas male poplars prioritize defense and stress adaptation. However, the molecular mechanisms driving these differences remain largely unexplored. In a recent study, Yan and colleagues uncovered a fascinating aspect of this dimorphism under salinity stress. They observed that male poplars secrete higher levels of citric acid, which facilitates the recruitment of specific bacterial species in the rhizosphere. These bacteria form a keystone node in the microbial network, positively correlating with the male plants’ health index under stress. In contrast, female poplars showed a different interaction: fungal keystone nodes negatively correlated with their health index, suggesting harmful microbial associations. This study sheds light on the sexually dimorphic responses in plants and the intricate dynamics of plant-microbe interactions. It also highlights how poplars deploy a “cry for help” strategy to recruit beneficial microbes under stress conditions. (Summary by Ching Chan @ntnuchanlab) Plant, Cell & Environment 10.1111/pce.15350

Plants actively shape the microbial community in their rhizosphere to optimize nutrient acquisition and enhance resilience against environmental stresses. Interestingly, in dioecious plants, male and female individuals play distinct ecological roles and evolve different environmental adaptability. For instance, female poplar trees tend to allocate more resources to vegetative growth and reproduction, whereas male poplars prioritize defense and stress adaptation. However, the molecular mechanisms driving these differences remain largely unexplored. In a recent study, Yan and colleagues uncovered a fascinating aspect of this dimorphism under salinity stress. They observed that male poplars secrete higher levels of citric acid, which facilitates the recruitment of specific bacterial species in the rhizosphere. These bacteria form a keystone node in the microbial network, positively correlating with the male plants’ health index under stress. In contrast, female poplars showed a different interaction: fungal keystone nodes negatively correlated with their health index, suggesting harmful microbial associations. This study sheds light on the sexually dimorphic responses in plants and the intricate dynamics of plant-microbe interactions. It also highlights how poplars deploy a “cry for help” strategy to recruit beneficial microbes under stress conditions. (Summary by Ching Chan @ntnuchanlab) Plant, Cell & Environment 10.1111/pce.15350